Fit for a King

Rare footage and new insights illuminate Elvis Presley’s life and work in an HBO documentary that, Priscilla Presley says, reveals “his heart and soul.”

Elvis Presley's big breakthrough, some reckon, wasn't when he scored his first hit single; it was when he competed in his Memphis high school's talent contest.

Until then, most classmates didn't know that this quiet boy from a poor family sang. But after performing "Till I Waltz Again with You" in that captivating voice, he won a thundering ovation, first prize, and, as he stated, a lot more friends.

"The moment that applause broke through, that's probably the first real validation that he's had," says singer-songwriter Tom Petty in the new HBO documentary Elvis Presley: The Searcher. Petty hypothesizes that it also lit the way forward, as in "That's what I'm going to do."

Presley appreciators should revel in The Searcher as much for what it reveals about him as for what it doesn't. This documentary does not dwell on his pill popping. The kitschy films. The rumored affairs with costars. All those tabloid-fixated aspects of Presley's life — which have undermined his legacy as an extraordinary singer-musician — serve as mere footnotes here.

Directed and produced by Thom Zimny and written by Alan Light, this three-hour, two-part documentary, which debuts April 14, instead embarks on a deep and thoughtful examination of Presley's life in direct relation to his singular musical career. The film puts his music at the forefront, tracing it to his roots and through those who accompanied him on his journey, including record producers, band members and session players.

"We had an early conversation," Zimny says, referring to producers Jon Landau and Kary Antholis. "Let's make sure that everyone who's talking was there, either in the studio or in his life in a real way, or because you truly believe," like Petty did, "that Elvis Presley changed their life."

Zimny, who won an Emmy Award for editing the HBO concert film Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band: Live in New York City, approached The Searcher with a clear vision of how he wanted it to look and sound. Using only voiceovers and no talking heads, he weaves an engaging and seamless visual chronology of Presley's life. "So that we truly are in the '50s era of Elvis, or the '60s," he says, and not suddenly jolted into, "Oh, there's the interviewee."

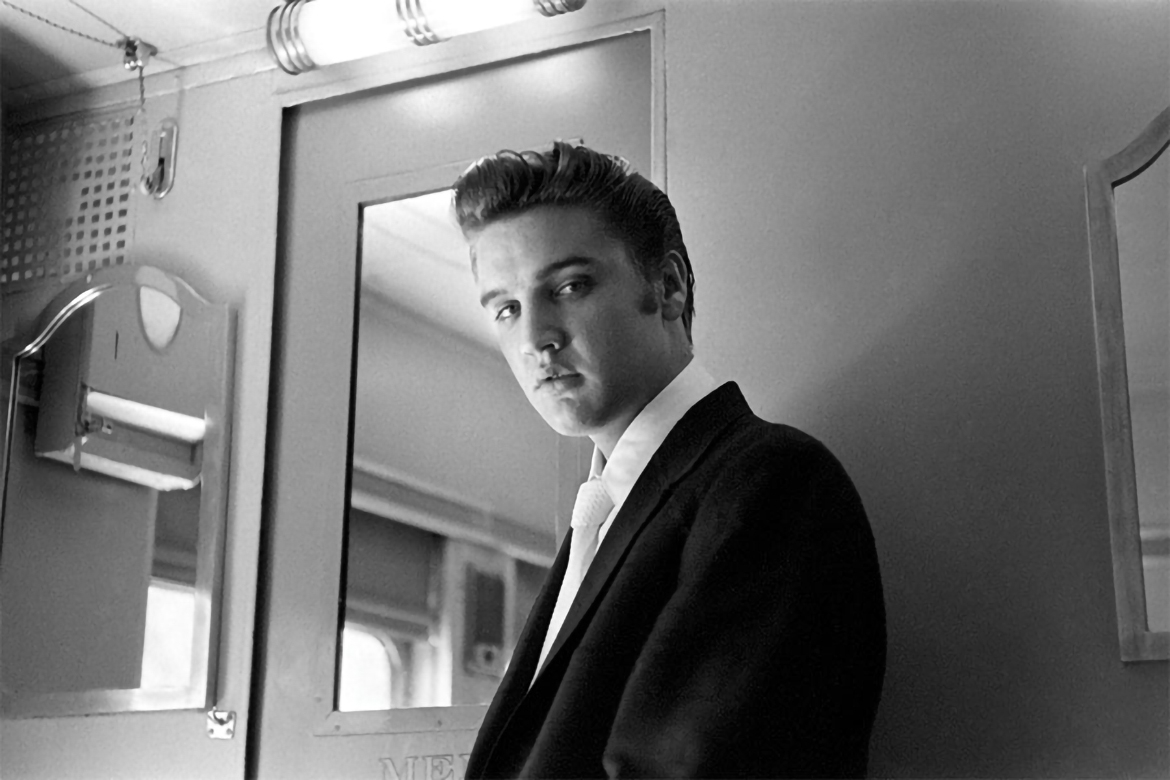

He also elbowed past the stale photos commonly associated with Presley. "One of the things I relied on," Zimny says, "were stills and footage that grounded you to an Elvis that didn't seem like the giant, iconic Elvis moments." He similarly refrained from taking a dog-eared greatest-hits approach to revealing Presley's rich musical legacy.

Years earlier, Ernst Jorgensen, an Elvis Presley catalog expert who served as a coproducer on The Searcher along with Zach Russo, had been allowed to open a locked filing cabinet in Presley's father's office at Graceland, the singer's Memphis refuge.

There, Jorgensen discovered all kinds of recordings. "He sent me 6,000 songs of outtakes of Elvis, including studio recordings, rare B-sides and live performances," Zimny says. "That was key in helping me dig deep into the catalog." It also, he says, "gives the ear something new to hear from Elvis."

That includes recordings from Presley's early performances on the show Louisiana Hayride, where he is on fire. There are rare audio recordings from when he served in the army and never-released cuts from his film Viva Las Vegas.

Another musical delight Zimny cleaned up for the documentary is Presley's appearance on a Frank Sinatra special, when they collaborated on a playful duet, taking stabs at each other's trademark lyrics.

There are also home recordings of him sitting down with friends at his piano and trying out material for what became his 1967 gospel album, How Great Thou Art. Priscilla Presley, his former wife, likewise gave Zimny access to never-before-seen photos, film footage and audio recordings that had been kept under wraps in the Graceland vault.

Among these were a family heirloom of Presley's mother, Gladys, singing gospel, along with rare clips of Elvis speaking. "I made available his voice. His own voice," Priscilla Presley says. "And when you hear that voice, you hear his sincerity. You hear his heart and his soul."

In one instance, Presley talks about how he discovered that his movements on stage provoked a strong reaction. It was his first live performance as a touring artist, "And everybody was hollerin', and I didn't know what they were hollerin' at," he says, explaining that once he got backstage his manager told him people were reacting to the way he gyrated his hips and legs. "I went back out for an encore and I did a little more," he says.

Although many early film clips demonstrate how Presley instinctively eats up the stage, camera operators rarely shot wide enough to provide a satisfying look at what was driving audiences wild. Presley bounces in and out of the frame.

While working on the documentary, Zimny says he became aware that camera operators weren't prepared "for this dynamo to come across the stage." He says, "So I actually see the cameras trying to keep up with him and the editing trying to keep up with him."

Priscilla served as an executive producer along with Glen Zipper, Jerry Schilling, Andrew Solt, Alan Gasmer and Jamie Salter. Zimny says that because Priscilla had known Elvis since she was 14, she was critical to helping him better understand the artist. "I was blown away by her knowledge and love," he says. "I really tried to make Elvis as close to the portrait that she was sharing in the room."

In a recent phone interview, Priscilla disclosed that she's been frustrated by the persistent caricatures and misunderstandings concerning Presley's lifestyle and creative choices.

"He didn't understand the critiquing," she says, referring, for instance, to his so-called "wiggle," which critics initially condemned. "Elvis felt that music. He experienced it, felt it and moved with it. It was never intended to be sexual. He didn't even know what he was doing when he moved. He was lost in his songs."

He was also unfairly ridiculed, she says, for his embellished Las Vegas jumpsuits. A costume designer came up with that concept because Presley was always ripping his suits on stage. After audiences expressed how much they loved them, he kept wearing them. "But it wasn't like he was trying to show off," she says. "He wanted to entertain. That's what he was there for — entertaining and, he always said, 'to make people happy.'"

She thinks Zimny got that and much more. "This is what's been needed," she says. "I truly believe that this is the definitive story of Elvis and his music." Zimny says what helped him connect to Presley was spending time at Graceland when the red ropes were down and no tourists were around to distract him from quietly roaming the premises.

"This is the home where he had his family. And this is where he recorded his albums. And this was his turntable." When he flipped through Presley's private record collection, he says, "I found a black gospel group, a folk singer, an opera singer. It was all there. He was taking it all in."

Sometimes Zimny just sat back and soaked in the atmosphere. "It was 3:30 in the morning in the Jungle Room, and you had to sit with that silence and say, 'Elvis sat here. What was he thinking?'" he says. "And by me being in that space where it actually took place, I feel like it brought me to the place where I made these choices to tell the story in a real way."

One key moment in Presley's life that Zimny wanted to recapture was the TV special Elvis, commonly known as his "'68 Comeback Special," which was intended to revive his singing career after years of making movies and not touring.

Priscilla told Zimny that Elvis had been a nervous wreck over it, fearing his audience wouldn't accept him back. And when they sat down in their Graceland living room in 1968 to watch it on air, she recalled, "Not a word was spoken."

Her insights gave Zimny the idea to film that setting and zoom into Presley's old RCA television screen (all of his furnishings have been meticulously preserved), then have it appear to be tuned to the '68 special. "It's chilling," Priscilla says. "The room is nostalgic. Seeing the camera moving forward on the TV and seeing him on that stage in that special — it's quite chilling."

At Graceland, Zimny also discovered an image of young Presley pausing on his bicycle on a country road seemingly outside Memphis.

"And slowly, as I'm building the film," he says, "I would return again and again to this image. For me, that was the beginning of this artist being on the road in some way. I thought it captured the searcher," who, Zimny explains, "is the person in this world looking to connect to music and looking to connect to a higher power through music."

Memphis was a music mecca when Presley was growing up. It's where he absorbed the various influences that coalesced in his particular sound. Zimny could easily imagine him as a kid biking past the music joints on Beale Street, where he'd catch whiffs of R&B, or turning on the radio to a country music station, or slipping into churches, as he often did, to listen to gospel. "He was always mixing genres," Bruce Springsteen says in the film.

Memphis is also where Presley made his first recordings at Sun Records. The Searcher tells some good stories about those days, like how Presley was initially too shy to venture into the recording studio. Instead he'd drive slowly past it, peeking in from his truck so many times that producer Sam Phillips and his staff began to wonder about him.

Zimny says he was acutely aware of the superficial and shortened version of Presley's catapult to fame, which is that he made hit records with Phillips, appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show and is credited with inventing rock and roll. "Everything in between seems to get lost," Zimny says, including acknowledgments of the black artists who heavily influenced Presley, like B. B. King and Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup.

"That's the sort of focus that I wanted to do," and he made sure The Searcher pays homage to many of those artists. The film also notes how Presley's appreciation of black music was unusual at the time. "Elvis was very different," says Petty on screen. "Color lines were rarely crossed. You just didn't find white people who tuned into black music and stayed and listened to it," the way he did. Elvis, he says, "longed to be a great gospel singer."

The second half of The Searcher takes viewers through the latter part of Presley's career, when he became more isolated. "He's trapped in a level of celebrity that we can't understand," Zimny says. "The tragedy that unfolded is that Elvis got less challenges and more distractions and at the end was exhausted."

Priscilla says watching the documentary gave her fresh insight into him. "Even I get a little emotional when I watch it," she says, "because he did the best that he could without having an equal who had the success that he had. He was on uncharted territory."

It is Presley's powerful and moving singing, however, that Zimny roars back to in the end. Again he tapped into the '68 special, listening to all the raw outtakes before choosing a passionate rendition of "If I Can Dream," a song written by Walter Earl Brown that includes quotes from Martin Luther King, Jr.

"The very last song," Zimny says, "was an amazing vocal for Elvis but also gives you that moment of redemption.

"I leave with that moment," he says, "because for me that's the height of Elvis the artist, and one of the most powerful healing moments. If you're going to the honest place of showing Elvis die and the tragedy that was lost, you want a moment when you can remember him as the active, searching artist."

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 3, 2018